REPORT ON WINTER 2003/4 - EXPEDITIONS

Summary

In winter 2003/4 four expeditions by camel were

undertaken. The objective of these ventures was to find additional proof for

the existance of Wilkinson´s 2nd Zerzura (Biar Jaqub) and to

define the boundaries of this “lost” oasis more precisely. In the course of

these investigations

a.

three additional roads leading from Biar Jaqub to the Tariq Abu Ballas (TAB)

and to ancient Mut el-Kharab were found

b. a segment of a parallel road to the TAB was

traced and

c.

the area of Biar Jaqub was better specified by the discovery of, in all, 149

important sites (not speaking

of about 700 additional observations such as the identification of ancient

road-signs). See list at the end of this report.

Report

My discoveries of the Tariq Abu Ballas (TAB),

of Djedefre´s Water-mountain (DWM) and of Biar Jaqub in the

field-seasons of winter 1999 – 2003 brought to light, that (contrary to traditional thought in Egyptology)

vast stretches of the desert southwest of Dakhla Oasis were not a fearful void

in ancient times, but an expanse that had been successfully traversed by Old

Kingdom donkey caravans on their way to the Gilf Kebir and, further, to the

Tschad Basin. In addition, in this empty sphere a “lost” oasis situated in two

days marching distance from Dakhla Oasis was identified; a striking evidence

that at least up to the beginning of historical times (and even later on) this part of

the Libyan Desert had been the home of an unknown number of oasis dwellers.

The discovery of Biar Jaqub made clear, that rumors

about the existance of a “lost” oasis (Zerzura) reported by Wilkinson in 1835

had a real base, and that native narrative should be thoroughly checked in the

field before being put aside as mere fairy-tale. In 1990, not just a rumor but

an astonishing “hard fact” was reported from a site 28 km south-southwest of

Mut, where Mrs. Walli Lama of Lama Expeditions (Frankfurt) had discovered an early Middle

Kingdom inscription of a high official named Mery. The translation reads: “In

the year 23 of the Kingdom: the steward Mery, he goes up to meet the

oasis-dwellers.” (Translation by

Günther Burkard, University Munich). Later, it turned out that the

site had been an ancient station on the TAB.

Were the “oasis dwellers” of Biar Jaqub the ones whom

Mery wanted to meet?

The 440 km long leg of the TAB so far

discovered, leads from the late Old Kingdom oasis capital Balat (situated in the eastern section of Dakhla Oasis) in

southwesternly direction via Mery´s rock and Muhattah Jaqub to Abu Ballas

Pottery Hill and further on to the Gilf Kebir, where the ancient caravan road

traverses the plateau. It descents from it into a subsidary of Wadi el Akhdar. DWM

is situated about 60 km north of the TAB. As far as examined until winter

2002/3 Biar Jaqub itself is stretching from DWM for about 8,5 km towards

the south-southwest. Would southern “outscirts” (if they ever had existed) of this not

yet fully examined “lost” oasis get into the reach of the TAB or even

touch it? As it is hard to comprehend that Biar Jaqub once upon a time was an

isolated oasis and, therefore, void of any continuous contacts with the outside

world: How was Biar Jaqub connected with the TAB, how with Dakhla Oasis?

Could traces of road links still be detected? These were the questions to be

answered in winter 2003/4.

First camel trip (Oct 18th – Nov 1st 2003)

On the first excursion I was accompanied by Marlies

Kriegler, a young Austrian student of meteorology. We had to cope with

tremendous heat. Our two camels were sweating severely and, shortly after the

start Marlies suffered from dehydration. Water consumption for humans and

animals was high.

Despite of these difficulties we succeeded in finding a line of road-signs (alamat) leading from DWM to the east. The alamat led us to a small flat-topped hill of about 6 metres in height. At this hill a quite comfortable road-station (Muhattah equipped with a large grinding plate) had been set up, most certainly dating to 4th dynasty times. The Muhattah is situated 13,2 km east of DWM. This distance lies comfortably within the scope of travel-ranges, that has been found appropriate for a one day march pensum of heavily loaded donkeys on the TAB. I christened the road “Tariq Khufu” (TK) and the station (according to the name of a scribe of Khufu´s expeditions) Muhattah Bebi (MB). Probably, the TK had been used by at least two Cheops-expeditions whose written records I discovered on 9th Dec 2000 at DWM.

|

|

| Muhattah Bebi (MB) viewed from south | MB (detail) |

About 1 km north of MB another line of old

alamat streches from west to east, indicating that the area of DWM was

connected with Dakhla by yet another ancient road. Until present no Muhattah

has been found on this trail.

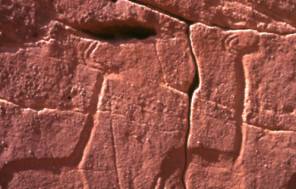

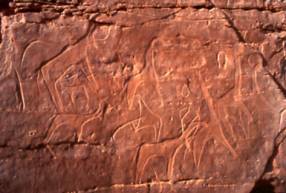

Because of the heat we could not follow the 2 roads further to the east. After replenishing our supplies at a water-dump, we investigated a hitherto untouched strech of land south of DWM. In this area 7 rock-art sites were discovered bearing images of animals and of steatopygeous female figures. One of the sites bears 3 extremly large representations of such individuals or godesses, their heads being adorned with elaborated hairdresses. These are figures which Hans A. Winkler attributes to a civilization defined as “Early oasis dwellers”.

|

|

|

Steatopygeous female figures |

Portrait of two steatopygeous female figures |

On returning from the southern vicinities of Biar

Jaqub to DWM we came across a flat pale-gray rock topped with 3 stone

circles. It´s northern rock face is decorated with a few severely eroded

petroglyphs, a few pieces of Sheikh Muftah pottery laying below at the foot of

the rock-art. On all but it´s western flank simple stone constructions had been

errected for storage (Khasin) and shelter. The site lies 13,2 km south-southeast of

DWM. This is exactly the same distance as found for MB a few days

before. Some well preserved pieces of pottery of the Abu Ballas-type in one of

the Khasins belonging to not more than one jar made clear, that the site had

been used as a Muhattah during the end of the Old Kingdom. Surprisingly, into a

few of the potsherds holes had been drilled. Therefore, the jar could not have

been used as a water container. Most probably it functioned as a food-storage.

I christened the site in reference to a name found at DWM “Muhattah

Sa-Wadjet” (MSW).

Was the site selected accidentally or was it chosen on

purpose? The distance of 13,2 km is startling. Were was the road? The terrain

is sand covered. Finally we found a line of Alamat that led us north to DWM.

Would there also be a leg of a trail leading from MSW further to the

south?

Second camel trip (Nov 19th – Dec 10th 2003)

On 19th November I set out with Johannes

Kieninger, Germany, and two camels for a second excursion. The heat had

vanished. Comfortable weather conditions led to a burst of discoveries.

2,6 km south of DWM we located a stone circle settlement consisting of 19 structures of stone slabs, obviously representing the remains of huts, the 20th having been erected in their center and marked with distinct cuts of copper(?)-tools. On a neighbouring conical hill a number of stone constructions that might have served some astronomical purpose were observed.

|

|

|

Stone circle settlement |

Stone slab with cuts |

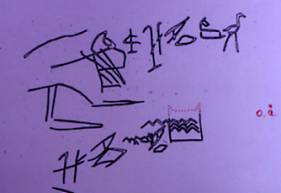

Not far away from the settlement two water-mountain symbols next to a steatopygeous female figure were found on a rockface. Most likely, one of the water-mountain symbols is a variant of the water-hole hieroglyph (the upper row of water-signs uniting, left and right, with the tops of the “container” walls); it also resembles the water-hole symbol connected with a hieroglyphic inscription of Mery, which was discovered by the French mission in the vicinity of Tineida (Dakhla-East).

|

|

|

Variant of water-mountain symbol resembling the water-hole hieroglyph |

Mery´s inscription with water-hole |

![]()

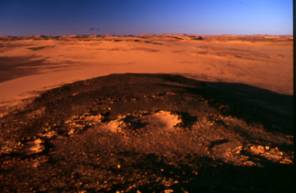

2,5 km further to the south a quite large stone circle settlement on a flat-topped hill measuring 90 x 40m was discovered. After finding (on a neighboring hill) another big stone circle settlement with stone slab-foundations and debris stretching into the plain, the conception that our small caravan had finally arrived at the “population center” of Biar Jaqub unfolded. Soon our vision was supported by the find of a cult place (field temple) adorned by a representation of a 1,27 m long “predynastic” sunboat, by beautifully executed representations of cows and of a “circle” of three addax antelopes. The disposition of the animals within the picture area bears great similarity to representations on a steatite and alabaster disc of King Den (1st dynasty, 2950 BC)

|

|

| Field temple: praedynastic sunboat | Field temple: Two cows and a calf |

Field temple: circle of three addax antelopes; steatite tisc of King Den; man

lifting

his weapon

|

|

|

Field temple: sandal |

Field temple: image of a hobble(?) |

On the surrounding hills further, smaller sized stone

circle settlements as well as a number of rock-art sites were detected. A few

hundred metres west about 1 sqkm of settlement-debris (fire places, bones, ostrich egg-shells, small pieces

of pottery, numerous grinding stones etc.) stretches

north to south. At the western fringes of this area we found a rock face (at high altitude of a hill) with

depictions of 3 water-mountain symbols. One of the symbols is of the same kind

as the one described above.

This group of sites accounts for the “population center” of Biar Jaqub. According to the number of “house structures” and the like it seems most probable, that once upon a time about 200 people had dwelled here. One might ask: Why such a densly populated area at this place? The sites are situated at the western outskirts of a large playa; a fertile area that would have been a suitable environment for collecting plants and for early forms of oasis agriculture. However, no depictions of such agricultural activities (as discovered at DWM) were detected around the field temple. Later, on the 3rd expedition, 1,5 km to the south-southeast of the cult place, two additional rock-art sites (one adorned with a representation of a “snake-dancer”) and another stone circle settlement on a flat-topped hill 1,5 km to the east of the field temple were found at the fringes of the same large playa. To make the wonder complete, we came across a line of alamat leading from the “population center” to the east (probably to Mut el-Kharab). We followed the signs for 19 km. This leg of an old trail attests for a second road between Biar Jaqub and Dakhla Oasis. Last but not least, on the 4th expedition, a depiction representing a fowling place was found in the vicinity of the field temple.

|

|

| “Snake dancer”-site | Snake dancer |

|

|

| Foulig place-site | Pictogram of a fouling place |

The discovery of the center of Biar Jaqub brings into balance several “indicators”: the number of wells, stretches of playa and the population “needed” to account for a place of “the oasis dwellers” in the late predynastic period as well as in early dynastic and later times.

Eight kilometres further to the south-southwest, in the neighborhood of MSW, we identified an area at the banks of a shallow wadi, where (at three rock-art sites) pottery (with white “inlays”) was found. Surprisingly, the pottery consisted only of “kitchen-ware”. Not a single water jar or pieces thereof were found. Would a natural water-source not have existed in that region in ancient times, we would most certainly have come across such remains. Among the rock-art were representations of a donkey(?), of sandals and of sheep.

|

|

|

|

Shallow wadi |

“kitchen ware” in shallow wadi |

representation of a donkey in shallow wadi; representation of sheep (left side of pictogram)

One of the constitutive elements of a florishing oasis

is the fact, that it should be connected with more than one destination of the

outside world. In addition to the segments of two roads leading to Dakhla (TK

etc.) we found traces of a hitherto unknown trail leading from Biar Jaqub to

Muhattah Jaqub on the TAB. When leaving the most southern outskirts of

Biar Jaqub, we soon came across a hillock marked with an alam. A cave-like

overhang on it´s eastern side contained fragments of an early-dynastic

Claytonring. In persueing our advance to the south, we soon found ourselves

walking on 15 thin lines of a donkey trail. After a while the grooves faded

away. While still on them we had come across a double-line of stones, 30m long (similar to those found along the TAB) and

in rectangular position to the ancient road. We followed the direction

indicated by the road fragments and finally arrived at a small depression (Wadi

Johannes; WJ).

On two hills in WJ stone circle settlements

were found, the bigger one of the two containing grinding tools. On a rock face

on the southern side of the settlement-hill a depiction of a big steatopygeous

female figure was discovered. From this evidence I concluded, that the

depression could have been the most southern outskirt of Biar Jaqub. We

searched in vain for a water-mountain symbol, a well or a spring. Finally, an

alam led us to a deep hollow close by, a location which might have harboured a

water-source in former times. The site is 38,8 km away from DWM and 25,2

km from Muhattah Jaqub on the TAB.

Stone circle settlement in Wadi Johannes (WJ); view from WJ to the south

Looking from the settlement-hill to the south one can

make out three prominent features: a pyramid-shaped hill enfiladed by two

rectangular formed black elevations. Not surprisingly, the “pyramid” is crowned

with an alam. At it´s foot a windscreen had been erected. Climbing on top of

the “pyramid” a conspicuous hill is seen far away in the south. This hill I

already knew. It is a noticeable landmark situated only 0,5 km north of

Muhattah Jaqub.

All landmarks, road fragments and alamat to the north

and to the south of WJ are in alignment with each other.

Leaving the “pyramid” and passing another alam on top

of a low but prominent hill, we came to a small resting place for caravans.

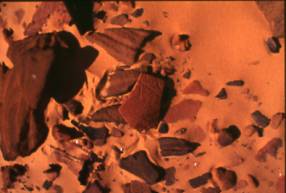

11.9 km before reaching Muhattah Jaqub, we stood in silence at the lee-side of

a pyramid-shaped hill and overlooked a wind-eroded terrain with scatters of Abu

Ballas-type pottery as well as of greyish/brown pot-sherds with sparkling white

“inlays”, fragments all too familiar to us as, just a few days ago, Johannes

had discovered two large pieces of such pottery forming a bowl at shallow

wadi. We had arrived at an important Muhattah which, most certainly, had

served as a resting place for the “oasis dwellers” of Biar Jaqub on their way

to Muhattah Jaqub. In reference to a name-fragment at DWM I christened

the site “Muhattah Ikepi” (MI).

Muhattah Ikepi (MI): view from the south; Abu

Ballas-type pot-sherds

MI: Biar Jaqub-type pot-sherds; site of the fragments of formerly errected stone constructions

There is a natural cleft of about a man´s height and a

man´s width on the lee side of MI. This fissure is almost 3m deep. Could

it have been used for suspending water-girbas that, if laid on the ground,

would have lost their fill rapidly due to the effects of osmosis? In front of

the crack one still can see fragments of formerly errected stone constructions.

Within and around these constructions the pot-sherds are scattered. Because of

the two different kinds of china there can be no doubt that MI, laying

almost half way between WJ and Muhattah Jaqub, had something to do with

activities of refilling the water jars on the TAB. Erosion, over time,

has caused severe destruction of the pot-sherds. No traces of recent visitors

to be seen. But, most important, the fragments of Biar Jaqub-type pottery give

proof, that along this trail movements of the “oasis dwellers” once had taken

place. I named the trail “Tariq el ma´a – the road of the water” (TM).

Proceeding on our way to Muhattah Jaqub we passed two

alamat at the midway-point (after 6 km). The scanty installation of road-signs on the TM

sharply contrasts with the elaborate setup of alamat on the TAB,

suggesting that the ones who had walked along the TM, had been at home

in the landscape which they traversed, while others heading for the Gilf Kebir

and for the Tschad-Basin, could have been strangers (Persons chosen at random by the oasis governor,

travellers or merchants who were not well aquainted with desert travel?) who

were in need of more “guidance” when traversing the vast void.

Almost all the pottery at Muhattah Jaqub, approx. 120

jars and a few pieces of “kitchen eqipment”, which I had discovered on March 5th

1999, were collected by archaeologists and stored in a magazine at Balat,

Dakhla Oasis. The “kitchen pottery” consisted mainly of a firmly walled, well

fired coop of anthracite/red-brown colour. The object has a clearly defined rim

and measures about 55 cm in diameter. It is very distinct from all other

pottery but not of the same kind as the pot-sherds of the Biar Jaqub-type

discovered at shallow wadi. I had found the coop on a shelf at the foot of

the fall of rock about 5 m above the desert ground. It was broken into a

handful of pieces and lay next to two semi-circles of stone slabs, which are

attached to the base of the steep rock. The latter indicate temporary

occupation and, possibly, represent a kitchen. This opinion is supported by the

fact that, as at a few other Muhattahs on the TAB, such “high

altitude-locations” for kitchens were probably chosen to avoid the spoiling of

food by dust and sanddrift while cooking and eating during the time of Khamsin.

A few spans east of the “kitchen” three “calendars”, sets of short vertikal

notches, are scratched into the rock. As if people, who had been ordered to

hold out at the site, had counted the days of their exile. To add some ease to

their difficulties, the same administration that had organized the transport of

the water jars from Dakhla Oasis to Muhattah Jaqub, to Abu Ballas and to other

Muhattahs during the 6th Dynasty, might have ordered the delivery of

the firm coop for the convenience of those, who had to endure hardship at this

lonely destination. These individuals left no traces of writing at the

rock-faces. However, an enigmatic ornament possibly representing a head-rest or

a spiral was found at the eastern end of the shelf. And on the hilltop a

sandstone slab covered with a puzzling arrangement of crude lines surrounded by

a cartouche(?) was stored in an alam, which had collapsed centuries ago. The

rock-drawing has close resemblance with my initials. Is this an attempt by

illiterate “oasis dwellers” to entrust a name to the rock, so that it would

outlast the passage of time? The two illustrations are the only works of art

that could be attributed to their presence.

Muhattah Jaqub viewed from the south; coop-sherds

Muhattah Jaqub: “calendars”; enigmatic ornament

Muhattah Jaqub: name(?) surrounded by a cartouche

The discovery of the ancient road (TM), which

connects Biar Jaqub with the TAB, leads to the following thoughts and

conclusions:

1.

The road adds additional proof to the fact that Bair Jaqub once was an oasis.

That this oasis existed in historical times, is attested by finds of Abu

Ballas-type pottery at shallow wadi and at MI. Greek(?) graffiti

discovered within the reaches of the oasis substantiate the view that Wilkinson´s

2nd Zerzura “florished” well into Ptolemaic times. After the wells

had fallen dry the notion of a “lost” oasis prevailed. It was handed down by

native narrative from one generation to the next until, in 1835, it was

recorded by Wilkinson.

2.

Surprisingly, only “kitchen-ware”, not a single water jar or pieces thereof

were found in Biar Jaqub. This alone is an indication that during an unknown

period in the past Wilkinson´s 2nd Zerzura was carrying water.

3.

The TM (tariq el ma´a) cannot be considered to be a side-track of the TAB.

Over a distance of 440 km the alignment of the Muhattahs on the TAB

deviates only by one or two degrees. This not only demonstrates, that precise

navigation during Old Kingdom times was profoundly exercised by up to date

unknown methods, but also that there was obviously no incentive to depart from

the straight line. The hardship of travel did not allow for angling away into

the unknown or to leave the beaten track for adjacent destinations. Under the

circumstances of desert travel such behaviour is nothing more than a matter of

common sense.

DWM and

Biar Jaqub are situated in three days marching distance west-southwest of

Dakhla. The distance between DWM and Muhattah Jaqub is 63,2 km due

south, the southernmost water-bearing(?) depression of Biar Jaqub being 38,8 km

north of the muhattah. Even nowadays long distance desert travellers bearing

the burden of walking and of driving pack animals would aim directly for their

destination (when heading

for the Gilf Kebir), therefore, following the hypotenuse-line of an

almost rectangular triangle instead of keeping to its cathetes.

4.

Whatever “the oasis-dwellers” carried on their donkeys along the TM, it

could have been nothing but water. Most probably were the inhabitants of Biar

Jaqub the ones, who were employed by the Egyptians to refill the jugs belonging

to the jar-deposits along the TAB. Accordingly, the TM was the

water-supply route for Muhattah Jaqub.

5. The discovery of the TM and of the afore mentioned pottery sites puts the Middle Kingdom inscription “the steward Mery, he goes up to meet the oasis-dwellers” into a new light. Obviously, Mery knew what he was up to. He did not convey to us, that he was going directly to an oasis but that he was going to meet people. Most probably, such a meeting took place outside a permanently inhabited area (otherwise the location would have been mentioned) at a site such as Muhattah Jaqub, to which the TAB as well as the TM are leading. To refill the jars deposited not only at Muhattah Jaqub but also at neighbouring water-storage places, would have afforded many days of work and would have involved quite a number of donkeys and men. Therefore, it seems probable that a small party of men stayed at Muhattah Jaqub during the period of water-refillment as attested by the “kitchen” and the “calendars”. These men were involved in carrying the water to neighbouring Muhattahs (e.g. Muhattah Umm el Alamat), while another party of “oasis dwellers” fetched the liquid supplies from Biar Jaqub via the TM.

The Mery-inscription therefore could be interpreted as a statement, that the steward was on an “inspection tour” to make sure that all the jars at Muhattah Jaqub and it´s neighbouring deposits were filled properly by the “oasis-dwellers”. In any case, Mery´s inscription is the first written evidence from pharaonic times suggesting, that a hitherto unknown oasis outside the Dakhla-Depression had existed somewhere in the west.

6.

There is reason to believe, that the steward Mery of the above inscription is

identical with the Mery of an inscription found by the French mission at

Tineida (Dakhla-East). The

latter text narrates the achievement of establishing a cistern or a pond in a

barren invironment. Mery´s “affinity with water” suggests, that he could have

been an expert, who had specialised in erecting places for water-supplies and

provisions as well as organizing their refillment. That such duties had always

been of great concern for the ancient oasis administration, became obvious when

the French excavation at Ain Asyl discovered a number of clay tablets. One of

them bears a complaint that the pottery intended to prepare the way for the

governor had not yet arrived at its destination. The pots were assigned to

serve to transport provisions for a longer desert journey.

7.

Prior the discovery of the TAB the

idea had been advocated, that Abu Ballas Pottery Hill was approached by ancient

caravans without touching intermediate restplaces. After a number of these

restplaces had been found, the idea of a “three-donkey-supply system” to

provide the TAB-Muhattahs with water was put forward. The theory runs as

follows: A caravan of three (thirty, threehundred etc.) donkeys plus drivers leaves from

Dakhla for the southwest. Arriving

at the first station one donkey-load is dumped. The disburdened

beast returns to Dakhla, while the two others continue their march. On reaching the next station the second

donkey is unburdened. He returns to Dakhla empty loaded. On his way back he

finds enough water and provisions dumped at the first station to complete his

safe return to the oasis. The third donkey advances to the third station and

dumps his load there. On his return to Dakhla he consumes parts of the

supplies stored at the second and at the first station. The author of this

theory believes, that such a sophisticated procedure could be continued

unlimitedly, therefore, making it possible to establish a line of depots across

waterless stretches of the Libyan Desert being hundreds of kilometres long.

As elaborate as

this theory is, it does not reflect the distribution of jars discovered in the

field. So far, only two main deposits on the TAB have been identified:

Muhattah Jaqub and Abu Ballas. All other water dumps consist of considerably

less jars and pot-sherds. Moreover, southwest of Abu Ballas the setup of

deposits becomes erratic. A sequent supply of the Muhattahs from a single

source originating in Dakhla would call for a distribution of jars much

different from what has been found in the desert.

Thanks to the

existance of Biar Jaqub the ancient water-supply scheme was much more simple.

There is yet

another supply-strategy to be considered, when contemplating about the setup of

ancient water- and provision dumps deep in the desert. In “Thousand-and-one

Night” a loading-scheme for a 40 days journey across the fearful void adviced

Musa Ibn Nusair to load 1000 camels with water-girbas, 1000 with provisions and

1000 with jars. Carrying pottery along deemed necessary, as hot winds from the

south would dry out the girbas. For that reason Musa was cautioned to store

water-supplies in earthenware. Most probably, the 1001-night story is based on

real observations however, passing from mouth to mouth, from camel drivers to

city-folks alien to the desert, the hard facts about water-storage in the

barren lands obviously became distorted.

8.

As attested by the find of Ptolemaic period pottery in a deposit of the TAB

and of Roman(?) graffiti discovered in Biar Jaqub, the supply of water from

Wilkinsons 2nd Zerzura via TM may have functioned well into

Roman times. Then, because of the greater reach of camels, probably only a few

muhattahs on the TAB were needed and maintained (e.g. a Muhattah in the vicinity of Khasin el-Ali). Most

likely, the TAB had been in use at least as long as water could be

obtained from Biar Jaqub. What has been attested by archaeological research so

far, is the fact that the TAB had been in continuous use for over more

than 2.000 years (from 6th

dynasty until the beginning of the Christian era).

9. As Wilkinson quotes the existance of “another wadi”, one might guess that the jar-deposit at Abu Ballas was refilled with precious liquid from yet another “lost” oasis. Traces of pottery marking a route to such a destination have already been found by the author.

10. The argument that depots of water jars at more than 30 stations on the TAB almost rule out the existance of any intermediate oasis on the route to the Gilf Kebir/Gebel Uweinat, for if one had been there, the expensive maintenance of Muhattahs over a 400km long stretch of desert would have been pointless, has lost it´s persuasive power. Such criticism does not acknowledge the evident rectilineal-oriented “urge” of the ancients to reach their final, far away destination. It also does not take into account a logistic system that, most certainly, provided provisions and replenishments not only from the starting-point of the TAB but also from it´s “flanks” (from a “lateral area of supply”).

11. The existance of a “lateral axis of supply” extenuates another critical appraisal. Taking into account that the vessels found at most Muhattahs are remarkable few, this critique rules out, that Egyptian caravans used the TAB engaging in “trans-Saharian” mining or trade expeditions. If, however, (constant or periodical) replenishment of water had taken place “from the flanks” of the TAB, the number of jars at most deposits would have been absolutely sufficient (The volume of 100 ovoid pots accounts for about 3.000 litres). Moreover, these well-fired jars could have been used over a long period of time.

12. The discoveries made in Biar Jaqub and the identification of a water-supply route to Muhattah Jaqub (TM) substanciate the conception, that Wilkinson´s 2nd Zerzura once was an important location for sustaining long-distance travel in ancient times.

For reasons of combing hitherto unexplored land we

choose a different course on our way back to Biar Jaqub. Soon we crossed an old

trail, which lead from the “pyramid” to the south-southwest and, later, we

passed a neolithic dwelling at a rock, where I detected a petrified jaw of a

hyena half-covered by a grinding plate. Heading north, a few singular stone

circles were observed until, 15,8 km south-southwest of DWM, I came

across a small rocky hill at the northern end of a playa pan on my midday walk.

It´s rock-faces are adorned with numerous steatopygeous female figures, their

different dresses and “haircuts” offering quite a glimpse at the

fashion-of-the-day at the end of the neolithic period.

Third camel trip (Jan 4th - Feb 2nd 2004)

On this expedition I was accompanied by my girlfriend,

Janine El-Saghir, who made a last minute decision to join. So, as in case of

the two journeys before, the expenses of the trip could be shared. We spent

about a week on photographic documentation of the sites discovered during the

previous surveys.

We also revisited a rockface at a hill which I had

discovered on February 11th 2002. It is adorned with a

representation of 4 Bohar Reedbucks facing a water-mountain symbol. Bohar

Reedbucks are distributed throughout the Sahel and are likely for Egypt during

the early Holocene (C.-S.Churcher).

They also live in Tansania. In the latter region they prefer swamp-like or, at

least, moist invironments. Would, therefore, the sole combination of a

water-mountain symbol with animals of this species account for a moist habitat,

for a spring or a well in the vicinity of the site? Would such a habitat have

prevailed in Biar Jaqub until the end of the neolithic period? Experts like

Toni Mills (Dakhla

Archaeological Project) are sceptical. The archaeologist supposes that the

representation of a single species at a water-mountain site is a mere

coincidence and not a proof for anything, particularly a specific habitat.

However, even at present, swamps and a lake do exist, for instance, a

stonethrow south of the capital of Kharga Oasis. Although no Bohar Reedbucks

rove through the reeds and rushes anymore, hunters are busy all year long

gunning down waterbirds. Contemplating about such scenes one wonders, which

species (extinct today

in the oases of the Western Desert) would return to their former

homes in the case of the absence of human beings and their efficient killing

devices. Had Count Almasy in 1937 not claimed to have shot the last Waddan at

Gebel Uweinat? When I traversed the Gilf Kebir in winter 2000/1, an individuum

of this species approached my caravan, proving that expert opinion should not

always be the last escape one must retreat to in order to understand the world.

All judgements are of transitory nature.

Four Bohar Reedbucks facing a water-mountain symbol; Bohar Reedbucks (close up)

On Oct 22nd 2003 Marlies Kriegler and myself had discovered the first leg of the TK and MB. Where would this trail lead to? Would it be equipped with Muhattahs similar to MB, each of them positioned at a day´s marching distance by donkey? Toni Mills had suggested, that a 4th dynasty trail connecting Biar Jaqub with Dakhla Oasis, should lead to the region between El Hindaw and Qasr Dakhla, where the Canadian mission had found an important Old Kingdom Muhattah for caravans coming from or heading for Memphis.

Departing from MB early in the morning, we set

out to the East and traversed a region of rough limestone. It took time until

we found a faint line of Alamat and, at midday, on higher ground, a Muhattah

alloted to two hills. The site which is only 8,4 km away from MB is

equipped with Khasins. One of them includes a grinding stone, the artefact

giving reminisce of the luxurious outfit at MB. With reference to the

name of the second scribe of Khufu´s expeditions at DWM I christened the

site Muhattah Ij-Mery (MIM). The stone constructions (places of rest?) were erected

on the northern side of the western hill, suggesting that this Muhattah served

as a day´s half-way station.

Muhattah Ij-Mery (MIM) from the south-east; close up

Continuing to the east we detected but a few alamat,

until we descented into flat land consisting of white “fishbone”-sediments,

sand and low dunes. Before entering the plain expanse I searched a whole day

for a muhattah, while Janine was herding the camels on a patch of dried bushes.

The muhattah was hidden in 16,7 km distance from MB and consisted of three

sandfilled windsceens erected next to a “prominent” landmark distinctive only

from the east (two

rectangular shaped white rocks). In it´s surroundings quite an amount of stone tools

and hearths as well as two house structures(?) were found. Surveying and

herding the camels in total silence and solitude, we had the impression that at

the time of Khufu´s expeditions the same place had served the donkeys for

grazing after a day´s march. As there was no ancient name left to be dedicated

to this Muhattah I christened the site Muhattah Janine (MJ).

Muhattah Janine (MJ); close up

The terrain ahead of us was void of any road signs. If

those had ever existed, they would have been swallowed by the sand. We crossed

the expanse, and arriving at the most eastern dune, we sloped into a strech of

land filled with numerous low sandstone hills. There, a set of alamat led us to

an ancient Khasin. I had discovered the site in March 1999 and, because of it´s

closeness to a pharaonic desert-patrol(?) station (nuqta; PDS) found in

February of the same year, had named it Khasin-Nuqta (KN). A number of

stone constructions, pots-herds, ancient wasms similar to the potmarks etched

into the Abu Ballas jars (here: carved into the rock) and a pharaonic figure (scratched on a sandstone slab),

that bears some similarity to one discovered by Toni Mills, pointed to a late

Old Kingdom date. Now, as we had succeeded in connecting the place with DWM

via the Tariq Khufu (TK), it became clear, that the Khasin must have

been approached by travellers and expeditions heading for Biar Jaqub already

during the time of the 4th dynasty. The site lies 33,5 km due east

of MB.

|

|

|

| PDS | Khasin Nuqta (KN) viewed from the East |

Toni Mills |

|

|

|

|

KN: pharaonic figure |

KN: ancient wasms |

From KN a faint line of alamat leads towards

Mut el-Kharab. As soon as we had ascended a stretch of high land, we passed

three limestone rock-outcrops to which the ancients had attached semi-circles

of stone slabs. The constructions were sand-filled. This site, erected close to

the rise, attests for the difficulties heavily loaded caravans had, when

treading the very soft ground of the ascent. I named the site, which is located

only 4,5 km to the East of KN, Khasin Musa Ibn Nusair (KMIN).

Section of Khasin Musa Ibn Nusair (KMIN )

We had run out of water. A city as busy as Mut we did

not want to enter with the camels. So, after passing a stone circle, pot-sherds

and a windscreen (14,9 km west

of Mut el-Kharab), we left the TK and turned north to El Gedida.

Half a day later we arrived at the newly drilled well of Bir el Dib about 4 km

south of the village. From there we turned west in search of a second road

connecting Biar Jaqub with Dakhla Oasis, a trail of which I had seen alamat

north of MB (see first

camel trip).

At the entrance to the desert (1km west of Bir el Dib) we had passed

a prominent hill scattered with pottery dating from Old Kingdom up to islamic

times. Thereafter an area of undulating land was traversed, in which fragments

of old roads were found, the larger part destroyed by modern quarrying

activities. When reaching the eastern limits of the plain, which stretches from

Gebel Edmonstone southward, our caravan was hit by a sandstorm. Leaving Janine

and the camels behind for a day, I cut north-to-south along the fringes of the

plain. Finally I came to three pyramid-shaped hills rising from the plain. At

the foot of one of the hills five stone circles in groups of two and three had

been errected, the area of the latter being filled with solid Abu Ballas-type pot-sherds.

To our amazement this site, which I named Muhattah Abd el-Kasus (MAeK),

is connected by alamat-fragments with PDS and KN, therefore,

attesting for a “side-track” leading to TK. Most probably, supplies of

water for TK were shipped from the area of Gedida via PDS to KN

in ancient times. This trail is another example for a “lateral mode” of

supply.

Muhattah Abd el-Kasus (MAeK) viewed from the west; view from the east

Group of three stone circles at MAeK; Abu Ballas-type pot-sherds

In the vicinity of the western limits of the plain we searched three days in vain for a trail running parallel to TK and for the above road, which Toni Mills had proposed to have, possibly, existed. In the rising land west of the plain we finally found a number of very old windscreens and pottery, sites that, at this stage of the investigation, cannot be attributed to definite trails.

.

.

South of G. Edmonstone: windscreen with

pot-sherds towered by an alam; two double windscreens

South of G. Edmonstone: stone circle

Finally, we had to make a guess, which one of the

sites could have belonged to the “parallel road”. Our assumption proved to be

valid as (following the

proposed direction of the parallel route to the west), we detected 2

mummified donkeys a few hours later. They had been covered by the dunes until

recently. What good luck that the sand had given away, so that we were able to

detect the beasts in all their splendor. As for their age one only can

speculate. It would be a sensation however, if these animals had toiled in a

caravan of the Kufu expeditions.

Two mummified donkeys

Back in Biar Jaqub an attempt was made to identify a

second ancient trail connecting Wilkinson´s 2nd Zerzura with the TAB.

We found a faint line of alamat, a few pieces of pottery and resting places

belonging to a road probably leading to Muhattah Arba´ Mafariq (MAM). We

followed this road (faint donkey

caravan tracks still to be seen in some places) for about 10

km, when a sandstorm lasting three days stopped further advances to the

south-southeast. The road runs past a group of conspicuous hills situated along

the western alignment of a plain containing fertile red playa. The plain is

about ten kilometres in diameter and is positioned adjacent to Biar Jaqub.

Later, I named the flat expanse Ard Chalil (AC), as my semi bedouine

friend, who accompanied me on the fourth camel trip, dreamt of dwelling here

one day and of running a farm. That AC is indeed in the process of being

prepared for agricultural production, is proved by a number of land surveyer

marks.

The notion that AC does not belong to the Biar

Jaqub area, was attested by rock-art void of human figures, of which we found a

quite sizable sample (3,5 x 2,5 m) representing (among others) giraffes; one

of the beasts depicted at the moment when dropping her baby. The rock-face,

which is bearing the scene, is oriented towards the plain, supporting the

impression that, once upon a time, AC had been the habitat of the big

mammals, and that this work of art was intended to mitigate the souls of the

animals chased and killed by pre-historic hunters. The site, which is topped by

a wind-screen (watch-out

post), is 24,9 km distant from DWM.

AC: rock-art 3,5x2,5m; rock-art 6,5 km distant from field temple

At the close of the expedition we surveyed the hills

along the fringes of the big playa east-southeast of the field temple.

In this region two stone circle settlements, pottery and a remarkable set of

rock-art sites (8) representing animals, human figures and abstract symbols,

were found. Were these symbols depicted by the same people, who had adorned

Muhattah Jaqub with an enigmatic ornament? The sites are 11,5 km distant from DWM

and 6,5 km from the field temple.

Rock-art 6,5 km distant from field temple

Fourth camel trip (Feb 27th – March 3rd 2004)

We started our survey in the vicinity of AC.

Next to the place, where Janine and I had been forced by a sandstorm to retreat

and to give up our examination, Chalil discovered a set of 4 Claytonrings.

Four Claytonrings

From there we continued south-east in search for the

proposed ancient trail to MAM. Soon we came to a solitary flat-topped

hill (27,2 km

south-southeast of DWM), on which 12 stone circles had been erected. At the

foot of a fall of rock (a permanently shady place at the northern tip of the hill) we

found pieces of pottery and a severely damaged dwelling. 2,5 km further to the

south-southeast, at a conspicuous group of elevations, another Claytonring site

and six stone circles on top of a high hill were detected. It is not clear,

wether these sites and another locality 1,3 km further to the west, furnished

with Sheikh Muftah pot-sherds (a huge, flat, solitary sandstone slab covered with enigmatic wavy lines

and a few animals lay nearby and gave us the impression of a “sacrificial

altar”), were stations belonging to our road.

Solitary sandstone slab covered with wavy lines; Sheikh Muftah pot-sherds

A fruitless search for it´s continuation followed. As

temperatures rose, I decided to head immediately for MAM (in 19,5 km distance). After 13 km

we came across a segment of faint caravan grooves, and 4,5 km later we

traversed a clearly visible caravan-route running NE/SW. The road leads from a

site (MAM-2) in 3,3 km distance, where, in November 2000, I had discovered

Abu Ballas-type pottery, towards two low, flat-topped, white rock-outcrops (“mastaba-hills”) 1 km to the

southwest, the easternmost “mastaba” adorned with sandals, a human figure, 2

animals (their figures

crudely arranged in a circle) and a piece of rock-art of inidefinable symbolism. At

this site it became evident, that an ancient road parallel to the TAB

had been discovered. Wether this hitherto unknown trail combines with the TAB

at certain muhattahs or wether it is a fully autonomous road, has yet to be

analysed. I named the road-segment TAB-2.

|

|

| The site MAM-2 | Pot-sherds at MAM-2 |

Mastaba hill: pair of sandals: human figure

To make the wonder complete, two more modern(?)

caravan routes (found in March

1999) probably dating to the islamic period, run parallel to the TAB.

Fully occupied with the search for the ancient trail, I had paid no attention

to them at the time of their discovery. Does the TAB-2 traverse the

desert about 2,5 km north of the TAB, the two “islamic” parallel routes

(TAB-3 and TAB-4) do so about 1,5 km to the south.

One can only wonder about the volume of hitherto

unknown ancient traffic having traversed the vast void between Dakhla Oasis and

the Gilf Kebir/Uweinat area. Most certainly, all those tracks continue to

Ennedi/Lake Tschad Basin; a few alamat similar to the big road signs on the TAB

having been detected southwest of Gebel Uweinat in northeastern Tschad.

What was the purpose of, what caused the need for such

burdensome trade routes? Would it not have been much easier for the ancient

Egyptians to obtain their highly valued africana via the routes, which led

along the Nile to Nubia? However, the caravan routes are there. And the

supply-route from Biar Jaqub to the TAB is there as well. Only thorough

investigation and profound archaeological excavation will untangle the riddle

and give sound explanation for their existance.

Exhausted from tremendous heat we arrived in the

vicinity of MAM, where I had dumped 30 litres of water three years

before. The supply was still there. After temperatures had declined, our small

caravan crossed TAB-3 and TAB-4, traversed huge concentrations of

stone tools and remains of settlements (already known from former visits)

and, finally, came to a rock-art site, which I had discovered on March 8th

1999. On the same day, on rising headland a few hundred metres south of the

rock-art, a stone circle settlement was detected. I sent Chalil with the camels

to a patch of dried tamarisks nearby and studied the rock-picture, which

measures 2 x 2 m.

Rock-art southeast of MAM

Barring future discoveries yielding more precise

information, this pictogram is a key for providing reasons and rough dating for

the steatopygeous female figures, which Winkler had attributed to a

civilization defined as “Early Oasis Dwellers”. The rock-picture contains a

number of those figures as well as giraffes, addaxes, ostriches and other game.

Surprisingly, a hind leg of a giraffe and a neck of another one are cutting across

the bodies of two steatopygeous figures. Another giraffe, however, is

superimposed by two human representations. Obviously, the steatopygeous females

were depicted, when giraffes roamed the surrounding savanne during the early

Holocene.

Therefore, these representations can only be attributed to the Early Oasis

Dwellers/Sheikh Muftah-Civilization, if

a.)

steatopygeous traits would have outlived the period of

Winkler´s Earliest Hunters (which, in their later period, co-existed with the Early Oasis Dwellers) and

b.) if

steatopygeous features would have survived as the prevailing physical

peculiarity of females until the late Neolithic period. (Up to present, no burial of a female belonging to the

Early Oasis Dwellers has been found.)

Because of lack of water we had to hurry back to the

north the next day (3/28/2004). At

noon, a hot spell from the south, which lasted three days, hit our caravan. During this

samum water consumption rose from 3,5 litres to 12,5 litres per day and person.

Despite of the hardship we managed to survey the eastern fringes of AC

and a few solitary hills at it´s southern end. At the foot of a pyramid-shaped

hill two structures of stone slabs and pot-sherds were found. 1,5 km northeast

of this dwelling, at one of the “eastern hills”, a rockface had been adorned

with a representation of a cow and a human figure.

Rock-art “eastern hills” representing a cow and a human figure

The discovery of the rock-art site caused us to search for settlement remains in it´s vicinity. We found an astonishing number of such sites on two flat-topped hills (40 + 8 stone circles) in 1,35 km distance. Another settlement containig 25 stone circles was detected on a solitary hill in midth of the southern section of AC . Close to this site (33,3 km southeast of DWM and 28,4 km distant from the field temple) we passed another isolated hill adorned with the most elabourately executed rock-art seen on this expedition. The picture measures 3,5 x 2 m.

Rock-art at a hill in the southern section of AC

On our way to Bir 5, by-passing DWM, a last

discovery was made: four badly eroded depictions of donkeys in a line. As if

the beasts were walking in a caravan of Khufu´s expeditions. The rock-art site

is situated 2,75 km east of DWM. It marks the beginning of TK.

Epilogue

In addition to the arguments put forth in this report,

I want to remind the reader of some further aspects and observations, that

speak in favour of Biar Jaqub being an ancient “lost oasis”.

1.

In an archaeological paper (Egyptian Achaeology, No. 23, Autumn 2003, pp. 25-28)

Kuper and Förster report from their first field campaign at DWM. They

disclose that Stan Hendrickx (a well-known ceramic specialist) has identified

a small component of pottery (extracted from a trial trench) belonging to the Sheikh Muftah

group, a late prehistoric unit of “Early Oasis Dwellers” known from

Dakhla which continued into dynastic times.

2.

The same report states that the pottery types excavated are almost exclusively

restricted to cups, bowls and storage jars characteristic of the early Old

Kingdom. About the number and the function of the storage jars no information

is given. Barring future discoveries proving otherwise, it seems most

improbable, that a sufficient quantity of water-storage jars (none of them, so far found, suitable for the storage

of water; information obtained by personal communication with members of the

excavation team) to be dug out in the future, will ever account for the

water consumption of some 400 men of Khufu´s expedition. The lack of a sizeable

quantity of jars, therefore, attests for a well at or in the vicinity of DWM.

3.

It is a remarkable circumstance that next to Ij-Mery´s and Bebi´s text the god

Igai is depicted. According to K.P. Kuhlmann Igai was an Oasis God.

Another opinion considers him to have ruled the Western Desert region as a

whole rather than an oasis. If the first view prevails: would one be allowed to

interpret the occurance of an image of Igai as an indication, that DWM

and it´s surroundings had been considered as part of an oasis by the two

expedition leaders? If DWM and Biar Jaqub were not an oasis in ancient

times, Ij-Mery and Bebi could have easyly depicted another god.

4.

On this expedition a few water-mountain symbols have been found, which resemble

the water-hole hieroglyph to a great extent, therefore supporting the notion,

that such symbols were used for marking water sources in late prehistoric

times.

This winter´s explorations round up my research

concerning TAB, DWM and Biar Jaqub to a single big discovery.

P.S.: For reasons of protecting the newly discovered

sites no expedition-map is attached to this report.

List of 2003/4 - Discoveries

1.)

22 stone circle settlements and tells, some of them quite large (90 x 40

metres); a few of them forming “family” clusters

2.) 20 stone circle sites (watch-out posts, temporary

dwellings)

3.) 27 pottery sites

4.) 10 Claytonring sites (pottery of, at present,

unknown function)

5.) 43 rock-art sites

6.) 14 fragments of ancient roads

7.)

21 windscreens (simple stone constructions used for shelter at resting places

of caravans)

8.)

2 ancient Muhattah´s (important stations on two hitherto unknown supply roads)

9.) 24 empty(?) ancient deposits (a thorough check to be left to the archaeologists)

10.)

4 burial places

(The number of

finds exeeds the total of 149 because of cases of double counting.)

Copyright Carlo Bergmann, May 20th, 2004

Complement

My discovery of Djedefre´s Water Mountain was

published in Egyptian Archaeology No 23, Autumn 2003 pp. 25-28 by R. Kuper and

F. Förster.