Pharaonic desert police station. Muhattah Jaqub (Abu Ballas Trail): in situ arrangement.

In the background to the right my caravan resting.

Ever since the discovery of Abu Ballas "Pottery Hill" in the Western Desert of Egypt by Lieut. More and J. Ball in 1917 scientists have wondered by whom, how and when some 400 big earthenware jars were transported to the site of the hill which is situated in the middle of nowhere - about 180 km south-west of Dakhla-Oasis.

Did Prince Kemal el-Din in 1923 assume that the jars were relics of fairly modern times and that the markings engraved on them belonged to Bidayate-tribes, TL-dating carried out at the Max-Planck Institute, University of Heidelberg, Germany revealed in 1988 that some of the pottery belongs to Middle Kingdom period (12th - 17th Dynasty). However, how the jars got there remained a mystery.

In Middle Kingdom times camels were not common in Egypt. The main means of transport were donkeys.

Abu Ballas is marked on almost any map. Although no path in it's surrounding is visible it has been assumed that the jars were used as a water-depot on a route Dakhla - Gebel Uweinat; a distance of 650 km across waterless wastes.

In 1909/1911 W. J. Harding King made several attempts to find old roads leading from Dakhla to Gebel Uweinat (Geograph. Journal, LXV, 1925 pp.153-156). He found some piles of stones set up as landmarks, a camel-road and a stone for crushing grains (marhaka). Obviously this route had nothing to do with the earthenware at Abu Ballas (discovered 6 years later) as Harding King did not succeed in finding pottery of the "Abu Ballas type" on this track. Also did he not focus his attention on donkey routes. The last attempt to disclose the secrets of ancient caravan-routes leading across the Western Desert of Egypt and to unvail the mystery of Abu Ballas was carried out by the French explorer Theodore Monod in 1993. He did not succeed (see Sers, J.-F.: Theodore Monod - Desert libyque. Paris 1994)

Despite of such failures I articulated the following working hypothesis: "The trade caravans of the Old Egyptians traversed the deep desert by the help of donkeys in order to reach far away destinations in Waday, Borkou and the Lake Tschad-Bassin" (see also P. Borchardt 1925; M. Fresnel 1850).

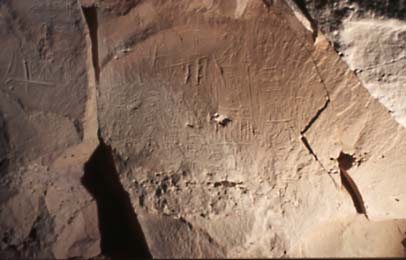

In Jan. 1999 I set out alone with my caravan in order to find proof of my theory which, in discussions whith Egyptologists, caused them to smile. In March 1999 I finally succeeded when I discovered an ancient donkey road deep in the desert on which I found three waterjar-depots of the "Abu Ballas type", a small number of hieroglyphic inscriptions and on a hill 15 km southwest of Mut (Dakhla) a pharaonic desert police station with jars, head-rests and a hieroglyphic text. This check-point is the first ever found in the Egyptian Western Desert.

Pharaonic desert police station. Muhattah Jaqub (Abu

Ballas Trail): in situ arrangement.

In the background to the right my

caravan resting.

There were no car tracks around. Many jars were still complete. They bear markings of the kind discribed by Kemal el-Din. Some of these markings repeat themselves from one water depot to the next.

Until January 2001 (on two more camel-expeditions) I succeeded in tracing the ancient Abu Ballas Trail from its beginning at the 6th Dynasty oasis-capital "Ain Asil" (Dakhla Oasis) to the western fringes of the Gilf Kebir Plateau, a distance of appr. 440 km. I came across 27 pottery-sites and water-stations.

My findings reveal that an organization of considerable size had been in charge of supplying the caravans of the ancients. In addition, I discovered a load of jars orderly deposited by a donkey caravan 3.500 years ago. On one jar the motivs of two donkeys are to be seen. The jars were laid on a saddle bag; organic material from which C-14 data was obtained and used as an age-check.

Muhattah el

Homareen (Abu Ballas Trail); in-situ arrangement and image of a donkey

on a jar

In January 2001 my expedition ran out of water. Camels and man had to return to Dakhla oasis.

B. DISCOVERY of DJEDEFRE`S WATER-MOUNTAIN

From the pharaonic desert-police station (see Chapter: A. The Discovery of the Ancient Abu Ballas Trail) a dim line of ancient road-signs (Alamat) points westward. Could such an arrangement have made sense to anyone in ancient times?

Since 1835 when Sir Gardner Wilkinson published two quotes from native narrative about the whereabouts of a so called Zerzoora (a lost oasis) in his book "Topography of Thebes and General View of Egypt" it is clear to anybody who takes oral tradition serious that there must be something in the west of Dakhla Oasis that provided a cause for never ending stories.

The two quotes run as follows:

:"...Zerzoora is only two or three days due west from Dakhleh, beyond which is another wadee; then a second abounding in cattle; then Gebabo and Tazerbo; and beyond these is Wadee Rebeena; Gebabo is inhabited by two tribes of blacks, the Simertayn and Ergezayn"

"About five or six days west of the road from el Hez to Farafra is another Oasis, called Wadee Zerzoora.abounding in palms, with springs, and some ruins of uncertain date. The inhabitants are blacks."

For Count Ladislaus E. Almasy, a Hungarian, and three adventurous British citizens (Sir Robert Clayton East Clayton, Hubert G. Penderel and Patrik Clayton) these quotes had a meaning. From 1932-1934 they organized expeditions and set out for Zerzoora. Finally they discovered three "green wadis" in six days distance close to the Libyan border (northwestern section of the Gilf Kebir-Plateau). With this find the world believed that the mystery of Zerzoora had been unveiled. However, where was the Zerzoora "two or three days west from Dakhla" referred to in Wikinson´s first quote?

Astonishing, the presumed location of this site correlates with an information about a stone temple given to Harding King in 1910. This stone temple, natives of Dakhla told the British explorer, could be found in "...eighteen hours´ journey west of Gedida in Dakhla Oasis".

Could it be that the line of Alamat I had observed at the pharaonic desert-police station led to this "temple"?

It took six attempts to detect the ancient trail (a road which had completely faded away over the millenia) and to find the site.

The "stone temple" revealed itsself as a conical hill about 30 metres high and 60 metres in length. On its eastern side there is a natural terrace. This plattform which has an average width of 3 metres and a length of approximately 35 metres is about 7 metres above the ground and fenced by a dry wall of stone-slabs. From the distance the place has some resemblence with the nabataean rock-palaces and -tombs at Petra.

Djedefre´s water-mountain - view from the east

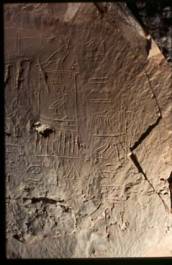

When setting my foot onto the terrace my eyes glanced over a breathtaking arrangement of hieroglyphic texts, of cartouches of Chufu (Cheops) and of his son Djedefre, of short notes from stone-masons, of two figures of a pharao smiting the enemies and of enigmatic signs ("watermountain-symbols") evidently placed on the rock-face in willful order. All these engravings were depicted in the midst of representations of animals and human figures from Prehistoric and Old Kingdom times. As pharao Djedefre´s name first cought my eye I christianed the site "Djedefre´s water-mountain".

|

|

Djedefre´s name and titles |

Example of a well preserved water-mountain symbol |

Hieroglyphic texts at "Djedefre´s water-mountain" explain the purpose of several 4th dynasty expeditions to the far away site. Two of the excursions took place during the 25th and 27th regnal year of king Cheops. His followers had come to the hill in order to quarry pigments.

Inscription of Iji-Meri and Bepi (Old Kingdom, 4th

dynasty) - total view and detail

Implications of the find

With Djedefre´s water-mountain the first 4th dynasty installation in Dakhla Oasis comes into light. Therefore, the time-span of Egyptian presence in all of the oases in the Western Desert is now enlarged by 300 years (from the 6th so far known to the 4th dynasty).

The Turin Papyrus states only 23 regenal years for pharao Cheops. Djedefre´s water-mountain might yield a first proof that the regency of Cheops was longer.

Early expeditions of the Egyptians in the Eastern Desert are well documented. Now, for the first time, there is an answer to the question why the Nile Valley civilization began to focus it´s interest on the oases of the Western Desert. The Egyptians of the 4th dynasty ventured there for prospecting mineral resources such as pigments. The latter were used for embellishing the gigantic pyramid complexes with their adjoining necropoleis.

C.

BIAR JAQUB

DISCOVERY of

WILKINSON`S 2nd ZERZOORA

Djedefre´s water-mountain is situated in an area where, according to J. Ball no "lost" oasis could be found as, in his judgement, interbedded clays between layers of Nubian Sandstone are missing.

Quote Ball:"There is as yet no evidence, so far as I know, of any well or spring maintained by local rainfall existing or ever having existed in the sandstone-country which forms the south-western desert of Egypt, except in the mountainous tract around Arkenu and Oweinat, and . it would appear unlikely that any "lost" oasis owing its origin to local rainfall can await discovery in that region." (Ball, J.: Remarks On "Lost" Oases Of The Libyan Desert. Geographical Journal. Vol. ........, S. (3)

Surprisingly, these layers of clay come into light at the rock-face of Djedefre´s water-mountain and elsewhere in that region. The clays hinder water from local rainfall to penetrate deep into the sandstone, therefore, promoting the development of underground water resources that could have been tapped by the ancients or that would have formed natural outlets at topographically favourable places.

Relics of up to 9 metres mighty layers of playa (native soil) which topped areas of flat sandstone territory were found in the vicinity.

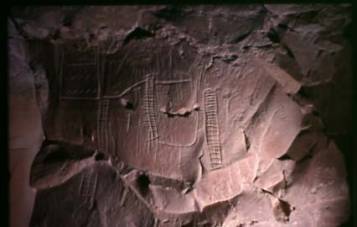

Evidently, the "water-mountain-symbols" at Djedefre were placed on the rock-face in willful order. In one cluster of "water-mountain symbols" closed vertical double lines with numerous horizontal strokes are incorporated (see picture on the left below). Could they be interpreted as check-lists (e.g. a book-keeping system which could have accounted for rations of water or units of pigment delivered)? In two cases, the mysterious pictogrammes are connected with a "water-mountain symbol" respectively a double waterline. (One closed vertical double line bears an appendix of crude hieroglyphic writing which, in May 2003, was translated by Prof. Miroslav Verner (Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, Prague) as: " Sa - Wadjet" - "Son of (Cobra-Godess) Wadjet", a customary name from Middle Kingdom to New Kingdom times. - see picture on the right below.)

Map fragment at Djedefre´s water-mountain and

inscription of Sa-Wadjet

After a second thought I interpreted the arrangement as a map. Dating most probably to Late Neolithic period the "map" shows 10 wells and a number of irrigated fields, two of them connected with a water-source. (One of the wells is superimposed by an animal of the neolithic pictorial canon suggesting that the map is older than Pharaonic.)

Water-mountain symbol superimposed by an animal

This map led me to Biar Jaqub where I (on two expeditions) identified the locations of all the wells. They and the surrounding area comprise an ancient "lost" oasis (Wilkinson´s 2nd Zerzura). The map, therefore, is the oldest one in the world.

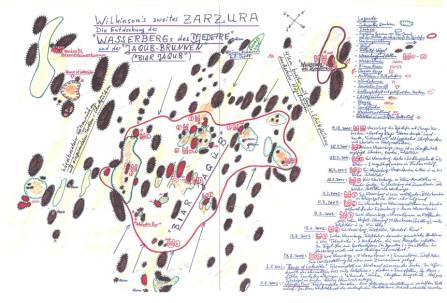

Author´s scetch-map of Biar Jaqub (enlargement possible in www.carlo-bergmann.de)

The area of Biar Jaqub and of Djedefre´s water-mountain represents the biggest rock-picture archive between Dakhla Oasis and the Gilf Kebir plateau.

The map at Djedefre´s water-mountain presents examples of wells connected with irrigated fields by means of small canals. Therefore, in the view of the Neolithic people themselves, the wells were either water-holes, artesian springs or springs that disposed their charge from nearby "horizontal" groundwater-reservoirs. In any case, the arrangements of wells, irrigation canals and fields are the first in situ evidence of an "early agricultural report" from Neolithic times. (As proofed by the inscription " Sa - Wadjet" - "Son of (Cobra-Godess) Wadjet" the area was visited until Middle Kingdom times. To the extreme this could mean, that "Sa - Wadjet" still cultivated crops in Biar Jaqub. As the aforementioned name is depicted adjacent to an irrigated field symbol the whole arrangement could be read as: "irrigated field of Sa - Wadjet". According to Prof. Verner this reading is a good choice within a narrow range of other possible interpretations. If Sa - Wadjet really cultivated his field in Middle Kingdom times this fact could have far reaching implications for the prevaling holocene climatic model of the Eastern Sahara.)

As proved by similar finds at Abydos (symbols of irrigated fields on tiny clay- or ivory-palettes; see Dreyer, G.: Umm el-Qaab I. Das pädynastische Königsgrab U-j und seine frühen Schriftzeugnisse. Mainz 1998) the representations used by pre-dynastic people for artesian wells and irrigated fields were, later, incorporated into the hieroglyphic language. Being depicted at Djedefre´s water-mountain and at Biar Jaqub, therefore, is striking evidence that the Western Desert of Egypt was one of the places where the development of the early stages of the hieroglyphic language took place. Hence, the area of Djedefre´s water-mountain and Biar Jaqub can be considered as one of the possible birth places of the hieroglyphic writing system. The author believes that at the end of the Neolithic wet-phase (with the influx of drought-strikken desert dwellers) these early roots of hieroglyphic writing were transfered from the desert to the Nile Valley.

In 1937/38 Hans A. Winkler, a reknown Swiss expert on rock-art in the Egyptian deserts and a member of the Sir Robert Mond Desert Expedition made a discovery in the vicinity of the Darb el-Ghabari (a few kilometres east of Dakhla). The petroglyphes he found resemble the ones in Biar Jaqub. (Winkler, H.A.: Rock-Drawings of Southern Upper Egypt. Bd. 2, London 1939. Pl. XXXIX und Pl. XLV; www.carlo-bergmann.de - supplement)

|

|

|

|

|

Biar Jaqub: pair of figures |

Winklers plate XXXIX |

Winkler´s plate XLV |

From this find and similar ones in the vicinity Winkler draw the following conclusions:

S. 17: "An archaic civilization has been discovered near Dakhla. These people are called in this report Early Oasis Dwellers."

S. 28: "In nearly all cases the women represented are pregnant. They are carefully dressed in long skirts in most cases covering the feet. These skirts sometimes display various patterns. It is apparently woven work. The upper part of the garment is as a rule neglected. As a rule the pregnant woman is shown in side view, sometimes in front view. In both views there are pictures displaying a kind of "divided skirt". These woven skirts are occasionally ornamented by bunches of short strips. Strings hanging down from the waist are the next peculiarity sometimes to be observed. Necklaces (?) occur but once."

S. 30 f.: "I suppose that they belong in some way to the cult of these Early Oasis Dwellers." (= Sheikh Muftah-civilization)...There is a certain similarity in style between the Uwenat people and the Early Oasis Dwellers. But here in Dakhla the exaggerating style is no longer balanced. The buttocks or in front view the hips of women are exaggerated out of all proportion.

To summarize. In the desert east of Dakhla are traces of early settlements in a depression which at that time was probably an oasis. These people were probably settled people and earned their livelihood from plant-cultivation. They used grindstones. The art of weaving was surprisingly developed. Statuettes of a pregnant woman were of high importance to these cultivators; possibly they were connected with the idea of a deity of fertility."

S. 35 f.: "These (Early Oasis Dwelllers) were plant cultivators. I have wondered, if possibly the women of the Earliest Hunters could have discovered by themselves the art of growing plants near some artesian well... But this is impossible. They are distinctly different people. As a whole they represent a much higher degree of civilization than the Earliest Hunters. the unimportance of cattle in their economics, their plant cultivation, their interest in the pregnant goddess, and their techniques are foreign to the Autochthonous Mountain Dwellers. This foreign .. people knew how to cultivate plants, smoothe stone, weave quite well, and venerated the pregnant deity."

To me there is no doubt that, before the time of the pharaoes and thereafter, a sedentary population left their traces at Djedefre´s water-mountain and in Biar Jaqub. Only a profound analysis of Biar Jaqub oasis, of the water-mountain symbols and of the petrogyphes representing irrigated fields and irrigation canals will, one day, transform Winkler´s astonishment

"The puzzle is to understand how the idea of cultivating arose here. Influence from outside the Oasis? From where? And if there is no foreign influence, the case is even more enigmatic"

into certain knowledge.

One thing, however, is clear to me by now: as no sizable amount of pottery for storing water has been found at Djedefre´s water-mountain the followers of Cheops and of Djedefre came to the "stone temple" and, probably, to Biar Jaqub because water from wells still could be obtained there during the times of the 4th dynasty.

Erosion has weathered out the mighty layers of playa in which the wells once were drilled. Wind has carried away the soil and with it the wells. So, only the water-mountain symbols at ten distinctly different locations in Biar Jaqub remind the spectator of today that there once was a small oasis which florished in two days marching distance southwest of Dakhla.

Implications of the finds

The breath-taking discoveries (of Djedefre´s water-mountain and of Biar Jaqub) have led to severe jealousy among a fraction of German archaeologists. Therefore, for obtaining scientific advice, I had to go abroad. Discussions about my finds led to the conclusion that the oldest history of the Egyptian civilization now occurs in a new light. Had (the Hungarian) Count Ladislaus E. Almasy presented sufficient proof in the 1930´s that the Libyan Desert was a cradle of the early Nile Valley culture, the conception of Herodotus that Dynastic Egypt is a child of the Nile has, in these days, to be modified. Because of my finds (including the discovery of the Abu Ballas Trail) it has become clear that, besides influences from the east, a massiv cultural influx from the Libyan Desert shaped the early dynastic period of Egypt.

D.THE ANCIENT (lost) "OASIS BYPATH" and the MILITARY EXPEDITION of CAMBYSES against SIWA OASIS (miscellaneous finds)

When Gerhard Rohlfs and his expedition returned from the desert to the Nile in April 1874 a congregation was held at the Institut E´gyptien over which the eminent German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch Bey presided. One of the questiones discussed in the meeting was the fatal end of Cambyses´ military expedition to Siwa. According to Herodotus the Persian army consisting of 50.000 soldiers disappeared in a sandstorm shortly after 525 B.C. So far, no traces of the ill-fated mission have been found.

In Drei Monate in der Libyschen Wüste. Kassel 1875 pp. 332-334 Gerhard Rohlfs summarizes the assumptions on the loci where the Persian army could have gone down with all hands. Although this summary had fallen into oblivion for many years it offers a still valid approach for finding a solution to the Cambyses problem.

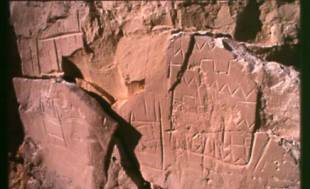

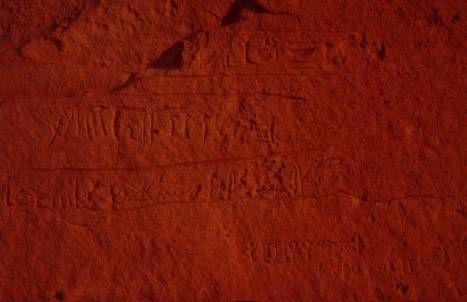

Since 1986, on half a dozen of expeditions, I set out in search for remains of the Cambyses army. So far, I have identified a 200 km long leg of the ancient (lost) "Oasis Bypath" (Oasenweg) on which I detected four dried up wells and the name of king Qakare´ (1st Intermediate Period). His name, so far, has been found in Lower Nubia only (see Zaba, Z.: The rock inscriptions of Lower Nubia. Prague 1974, pp. 160 ff.); an important hint obtained by field work where the "Oasis Bypath" leads to. On this route I came upon a resting place for ancient caravans. The location is thoroughly covered with hieroglyphic and hieratic texts. Some of the inscriptions can be dated to the time of Ahmose (18th Dynasty). One of the texts gives notice of a military move which might have to do with activities repelling the Hyksos. The resting place is the biggest inscription site so far found in the desert between the oases.

Oasis Bypath - fragment of an insciption at an ancient resting place

for caravans

The reign of Ahmose lies 1.000 years ahead of that of Cambyses. To me, it is good fortune that, while hunting for remains of the Persian army, I happened to come across a set of so far unknown ancient texts which reveal information about another famous military expedition.

E. DJARA - RE-DISCOVERY of Rohlfs´ DRIPSTONE CAVE and DISCOVERY of NEOLTHIC ROCK PICTURES

Despite immens (German government) funding of university-based research in the Western Desert of Egypt during the last 25 years (TU-Berlin: 30 Million EURO geological survey; University of Cologne: 20 Million EURO prehistoric survey) the area between the Nile and the oases (Libyan Limestone Plateau) has been thoroughly neglected. In fact, since the days of the famous German Expedition of 1873/74 led by Gerhard Rohlfs the region remained a scientific vacuum.

In his book Drei Monate in der libyschen Wüste. Kassel 1875, Rohlfs reports that, on 24th December 1873, his caravan passed by a dripstone cave. As Christmas Eve was only half a day ahead the expedition paid but a brief visit to the cavern. Djara, the site, was put on the map. No further details were given and the cave fell into oblivion.

Another chance for a European to visit Djara occurred in 1897 when examination and mapping of the Farafra Depression was undertaken by the Geological Survey of Egypt under Hugh J.L. Beadnell.

Quote Beadnell: "In December 1897, immediately after reaching Qasr Farafra, I found it necessary to communicate with the Nile Valley, and took the opportunity, fortunately being in the possession of a good measuring wheel, of crossing the desert in a straight line from Farafra to Assiut. From the Rohlfs Expedition map it was clear that Assiut and Qasr Farafra were almost on the same parallel of latitude and so after reaching the plateau above Bir Murr, I struck off nearly due east and steered and plotted my course by plane-table and compass, the distance being reckoned by the measuring wheel. Eight days after leaving Qasr Farafra we struck the cliff of the Nile Valley, having covered nearly 300 kilometres, and saw with some satisfaction that we were marching on a point not more than a few hundred yards on one side of Assiut."

Fully occupied with their measurements Beadnell and his team passed by the cave in approx. 10 km distance.

In Winter 1990 I was busy surveying old caravan routes on the Libyan Limestone Plateau east of Farafra. Following the footsteps of the German expedition of 1873/74 my small caravan finally arrived at the Rohlfs-Cave. Sliding down a sandy slope I entered the cavern and, to my surprise, discovered a big stalagmite densly covered with neolithic rock engravings. Nearby, covered by sand, more pieces of fine rock-art emerged. The petroglyphes represent the fauna then existing (6.500 -5.500 BC): ostriches, addax antelope, goats and other bovids.

After a further slide down I entered a large hall which extends over almost 50 metres; clusters of impressive stagmites hanging from the roof, the ground covered with sand. This was clear to me from the first moment: depending on the thickness of the sand-fill, the cave could have served as a sediment-trap for human debris, plants and animal relics for thousands of years.

On 24th December 1873 Gerhard Rohlfs and the members of his scientific staff almost scraped the rock pictures on the stalagmite with their shoulders. Neither the rockart nor the neolithic settlements (their outskirts only about 20 metres distant from the entrance of the cave) were noticed. With the discovery of these treasures 127 years after Rohlfs I felt like having pushed open a long hidden gate to an Ali Baba-like desert-enclosure from Thousand and one Night.

Up to date a team of prehistorians is excavating the spectacular site.

Djara - Rohlfs´dripstone cave - first inspection by scientists, to

the right the petroglyphe-stalagmite

This sequence of discoveries in the deep desert (not in the oases) outrivals the total sum of finds of all explorers of the past since World War I.

Currently my finds are leading to a re-design of prevailing opinion in Egyptology.

Copyright: Carlo Bergmann, August 30th, 2003